Our Story

Yesterday, someone said to me, “what? End of January already? Last year has flown by, this year will be the same.”

I replied, “you’re showing your age. Time seems to shrink, when you are getting older.” Though he ain’t much more than half my age.

At my age, in the mid seventies, one can retire. That’s not for me. Maybe if you retire, time isn’t flying past. One can also turn into a grumpy old man. Whether that’s the case with me, I leave to others to judge. But one thing probably all of us do occasionally, is, to look back not in anger, but with a certain amount of nostalgia. Particularly in winter, when the days are short. It’s a great time to go down memory lane. That’s what I would like to do in this, my first blog. To briefly sketch my wife Sheileagh’s and my life in Achiltibuie , in Coigach. To tell you our story. Nowadays, Coigach is a rather prosperous place. It wasn’t always like that.

Some people call the whole peninsula Achiltibuie, not Coigach. Achiltibuie is the village with the shop, and the church, and the post office, and at its entrance, the war memorial. But there are many more hamlets and townships, some with only two or three houses, two even without road access, which have been deserted many years ago.

When I came here fifty years ago, the salmon netting station was a centre of all the villages that belong to Coigach. It was a hive of activity, enterprise and inventiveness. There were three crews working three boats. The salmon boys were mostly just that - boys. Each of them strove to be one day a skipper.

After a couple of years or so, I became a salmon fisher, too. What had taken me here? Probably reading too much Hemingway in my youth. Looking for adventure. The lure of fishing. I loved it. We caught huge, glistening fish in their hundreds every day.

I was - it doesn’t bear thinking now! - a good looking guy with thick, curly dark hair. Today, there is very little left of my hair, and nothing of the fisheries, the former ravaged by old age and the latter by the fish farming industry and government edicts.

The first couple of years, I lived in a house right by the sea with a wonderful old lady called Abi Muir. At first, when she hadn’t been debilitated yet by a stroke, she made me a pot of porridge every morning. I ate it up. To eat everything up, that’s the way I was brought up as a nice middle class German boy. The following morning, there was more porridge on my plate. I ate it all. So the amount increased again. Until I had to give in. What a laugh we had! Just like when I cooked spaghetti one evening, which Abi had never eaten in her life. How to get these wormy things in her mouth?

She taught me everything that she thought I had to know about Coigach and its people, so that I could make the place my home. And by golly, I had to learn a lot! Sometimes, she even had to tell me off.

Then Sheileagh appeared on the scene. That wasn’t entirely a coincidence. Abi was her great aunt. Sheileagh didn’t grow up in Coigach. But there was a strong cu. Her father belonged to the Outer Hebrides, to the northern tip of the Isle of Lewis, one of the stormiest spots of the world. Education has always been number one in the Highlands and Islands. He went to university in England, in the historic cathedral city Durham, and became a nuclear physicist. He worked in Aldermaston, in Geneva and Edinburgh. That’s where Sheileagh spent her youth. But her grandmother belonged to Achiltibuie. Belonging used to, and still is, very important in this part of the world. I will never belong. But Sheileagh does. Why?

At this point, I have to relate an allegedly “well documented” story of Coigach’s past. Around 1760, there lived a miller by the name of Alan Ban at the Achnavraie burn, who had originally come from further north. He had seven daughters. The family was known as the Oichien. One day, he caught a banshee hanging out the washing, which was understood as a precursor of someone in the family going to die. Unless you manage to catch her. Alan Ban, quick as a flash, grabbed her and forced her to give him a promise that all his seven daughters would get married to Coigach men.

And so it happened. He became grandfather of 70 or 80 - here the well documented accounts vary - grandchildren. Whatever the true number was, going back to the Oichien, all the old Coigach families are related. Therefore Sheileagh is related to every one of them. Alan Ban’s youngest daughter was called Annabel (Barrabel in Gaelic). That’s her line. The name was carried right down through the generations. We even named our youngest daughter Annabel. But I am rushing ahead.

To cut a long story short, a cousin of Sheileagh subtly set us up, we fell head over heels in love and eloped to the Western Isles. Abi assured Sheileagh’s father - her nephew - that we would make a good match, and we got married before half a year was out. We moved into the house where we still live.

Before our time, the house belonged to a bachelor known as Big Hugh and his equally unmarried sister Mina. Judging by the stories that still are part of the local folklore, Big Hugh, sheep farmer and county councillor, must have been quite a character. After a disappointing sheep sale, when prices had fallyrock bottom, another of the old-timers told his fellow crofters (that’s what small farmers are called in these parts), “never you mind. If I win the pools, I’ll buy you all a ticket to America. I’ll just keep Big Hugh for a laugh.”

Of course he never did win the pools.

Big Hugh’s house, now our house, looks quite different today, We extended it not just once, but twice, no, three times. It became too small every time another child was born. We had one, two, three, then four. Four children per family was quite normal in those days. The village school was thriving, there were 36 pupils. Not like now, when there are just half dozen kids left and the local authority employs - goodness only knows what he’s meant to do - a “repopulation officer”.

The overall population of Coigach hasn’t shrunk. It probably hasn’t even aged. But young people think more about the cost of raising children and stuff like that. We just had them.

In wintertime, I was crewing for the wonderful Gillies Maclennan, who was precentor in the local Free Church and spent an awful lot of time singing psalms in the engine room of his boat, while trying to fix the starter motor or pondered, why the battery was flat. Accordingly, we didn’t catch a lot of langoustines, which is what we set out to do. The pay at the end of the week was meagre. But we had a lot of fun.

The time came when we had to grow up and earn some money. In the end, life in Achiltibuie is not all that dissimilar to life in London or Berlin. Okay, there is virtually no crime, which is wonderful. The surroundings are wonderful. But one still has to make a living. That only works, if you aim at something and work hard to achieve it.

Sheileagh had studied art. She became an itinerant art teacher. She taught in tiny schools all over the northwest Highlands. I called her the tinker teacher. Like the tinkers of old, she gleaned news in one village and carried them forth to the next one.

I had never learned anything properly in my life. So I dabbled in writing. Somehow it worked out. Magazine and newspaper editors paid me exceedingly well for what I came up with. Bingo!

I even wrote a book. A publisher asked me to base it on columns that I had written over many years in the German weekly Die Zeit. They run under the heading “Mail aus Achiltibuie” and appeared alongside Mails from Moscow, Mails from New York, Mails from Paris, and so on. They put Achiltibuie where it belonged to: on the map of the world. Commercially, the book wasn’t more than a very moderate success, though some people assured me that they liked its humour combined with sadness. Perhaps some things are better said in a brief form, than filling a whole volume with them.

And then we built the Brochs. That was the hardest thing we ever did. So many obstacles to overcome! So many sleepless nights! Objections of pesky neighbours, officious councillors and nit-picking pen-pushers in offices. It’s a miracle that the whole thing came together in the end. It only happened because of the incredible can-do attitude of a wonderful team of local builders, joiners and stonemasons, to whom everything was possible. However far-fetched our and the architect’s ideas may have appeared to them to start with.

A lot of things have changed since those early days when an adventure seeking young man, who had read too much Heminway, came here from Germany. Some for the better, some for the worse. Of course we were part of the changes. Perhaps we have even driven some of them. Some people, however, like my very close friend Kenny Maclennan, brother of Gillies, the Psalm singing precentor, with whom I went langoustine fishing, still embody what Achiltibuie always stood for in the way I saw it: individualism, self-reliance and a maybe sometimes stubborn independence of mind. With all that, Kenny is a highly successful sheep farmer.

And then there is of course the immutably timelessness and grandeur of the Coigach landscape and of the sea. Mostly silent and occasionally howling with the fury of a raging gale. Then the detritus of such a gale, ripped from the bottom of the seashore, is lying about on the beaches. Humans come, humans go. The landscape will never change.

But from the day to day life, that is my intention, I will give you an account in this blog.

This is a beautiful and very typical picture of Abi Muir, who taught me all there was to know about Achiltibuie and Coigach

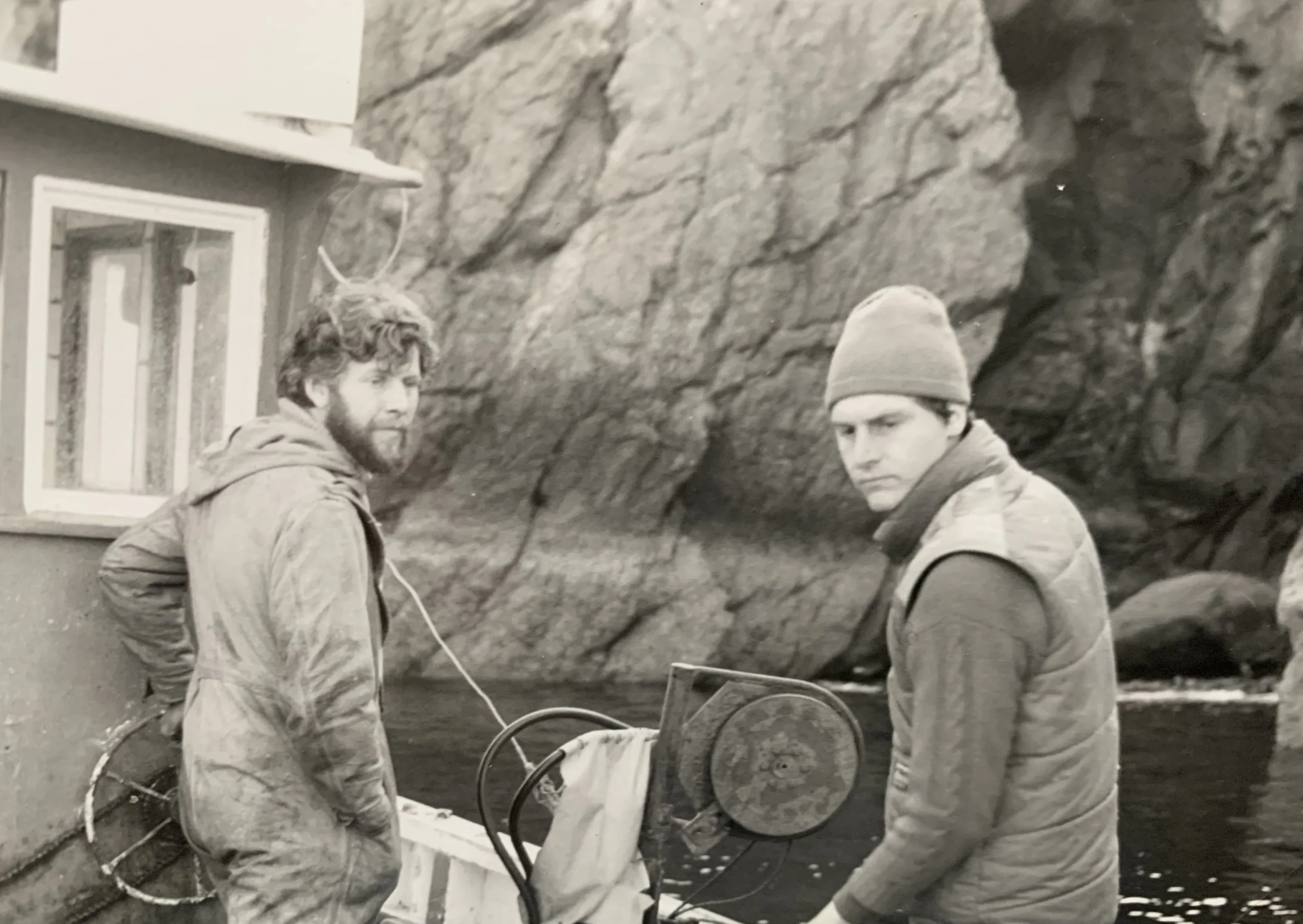

Gillies Maclennan and I fishing languages

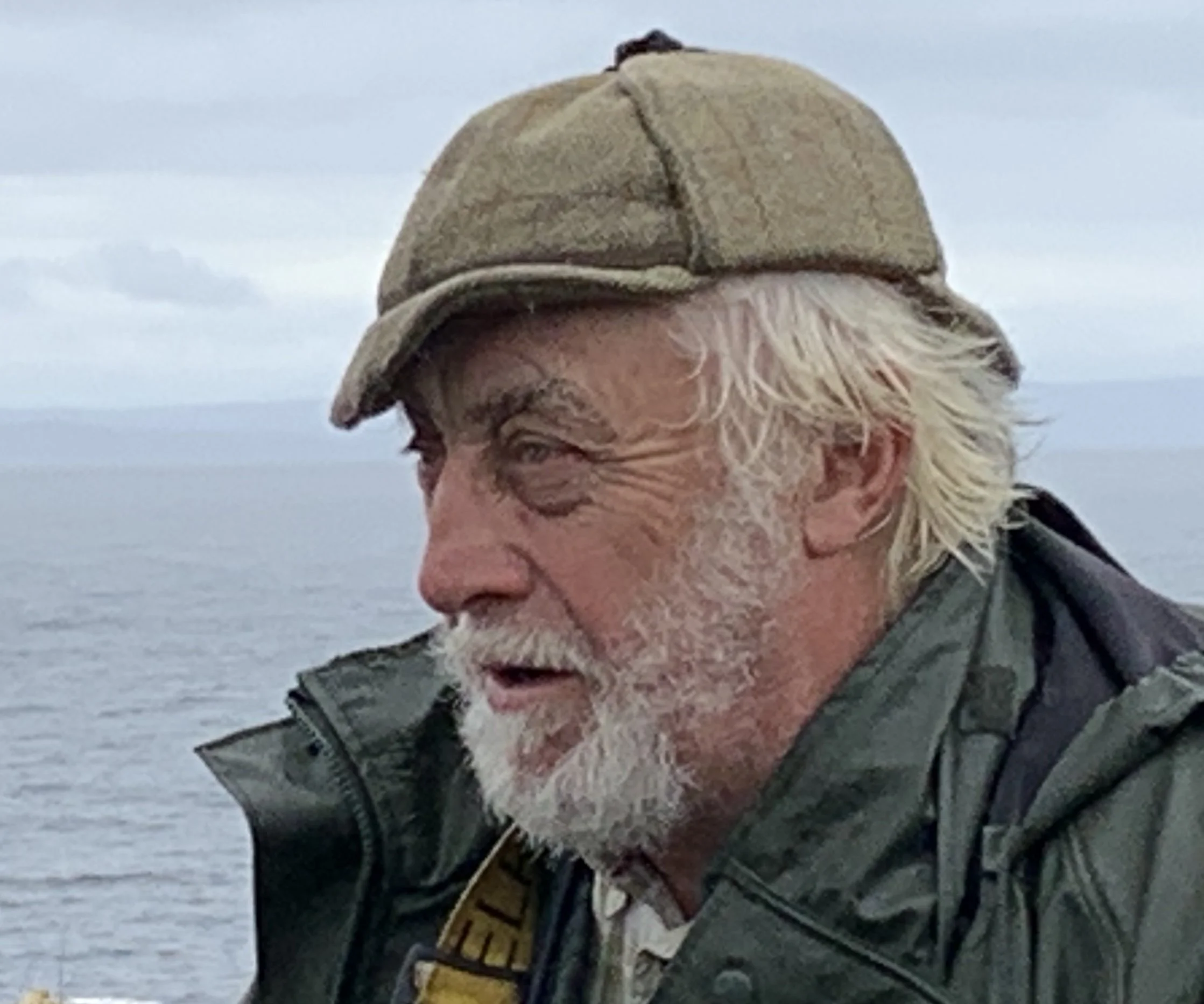

Gillies’ brother Kenny, sheep farmer and a very good and loyal friend

Big Hugh, former owner of our house, offering a sandwich with a gesture that says, I’d rather you wouldn’t take it

That’s me talking my future wife Sheileagh out in a boat, when I was a salmon fisher. In those days, it was meant to spell bad luck to take a woman out in a boat. It brought us good luck ever since.